From The BLOG

So You Want To Provide Citizens Access to Government InformationA background explainer and snapshot of the Access to Information community at this moment in time, Summer 2024.

A background explainer and snapshot of the Access to Information community at this moment in time, Summer 2024.

Campaigners have successfully passed Access to Information laws in countries around the world. The laws require governments to share information that journalists or other citizens request unless there’s a compelling reason not to. This information is used to uncover corruption and generally help hold governments accountable to their constituents.

Civic tech organizations have developed a class of web platforms that facilitate citizens’ ability to initiate, track, and follow up with freedom of information requests. The most popular platform for accomplishing this was started by mySociety as the WhatDoTheyKnow project. After open sourcing the platform as Alaveteli, it’s now been adopted by at least 30 organizations in countries all over the world. Alaveteli has helped citizens make over one million Freedom of Information requests in over twenty-five jurisdictions and twenty languages.

Access to Information laws and the programs they create vary, of course, in terms of their strength and governments’ responsiveness. Some are referred to as Freedom of Information (commonly abbreviated as FOI). Other, more restrictive laws facilitate “Access to Documents” rather than the broader Freedom of Information laws. There are also Environmental Information Regulations, which act like Freedom of Information laws for public access to environmental data. For the purposes of gathering this community across its diverse forms, we will use the more inclusive Access to Information term.

Organizations operating access to information platforms adapt accordingly to local conditions. For example, Alaveteli is usually hosted by civil society organizations. In countries where the government hosts its own freedom of information web platform, civil society organizations might guide people through those official channels instead.

Access to Info organizations work in difficult conditions to improve public oversight of their governments. In many places, the relationship with government offices ranges from benign neglect to actively adversarial. Despite serving journalists and other high-profile investigators of government conduct, the organizations facilitating the access to public information struggle for funding and broader awareness of their existence.

To galvanize this community and identify methods of peer support, mySociety and the Civic Tech Field Guide teamed up, with support from the National Endowment for Democracy, to form a Community of Practice. The network is facilitated by Jen Bramley.

We invited scores of Access to Info groups to participate to build and strengthen peer relationships. You can browse the gallery of member groups and their projects on the Civic Tech Field Guide’s dedicated section.

Last month, we took advantage of the fact that a good portion of the Access to Info Community of Practice was in attendance at mySociety’s The Impacts of Civic Tech Conference (TICTeC) to host a shoulder event together. Newspeak House generously hosted us in their London event space.

Although initially structured as an unconference, we quickly shifted to an open circle conversation, with Gareth Rees framing the conversation. This anonymized summary of some of the discussion is intended to provide a snapshot of the Access to Info Community of Practice in this moment in time, and an entry point to other Access to Info groups and their partners, whether in the Community of Practice or not, to keep up with the current state of the field. The writeup may also be relevant to other coalitions and partner networks operating in other domains.

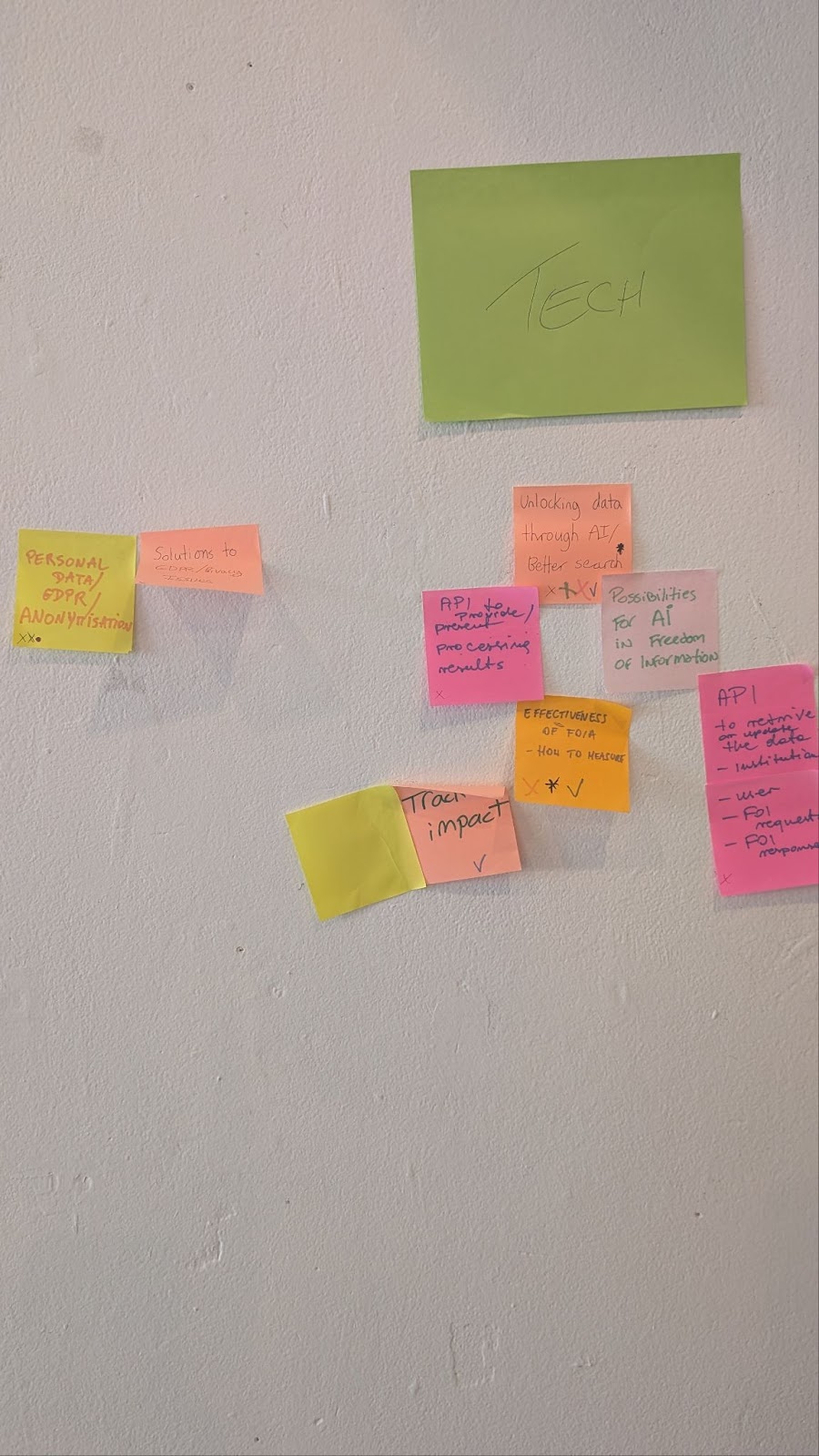

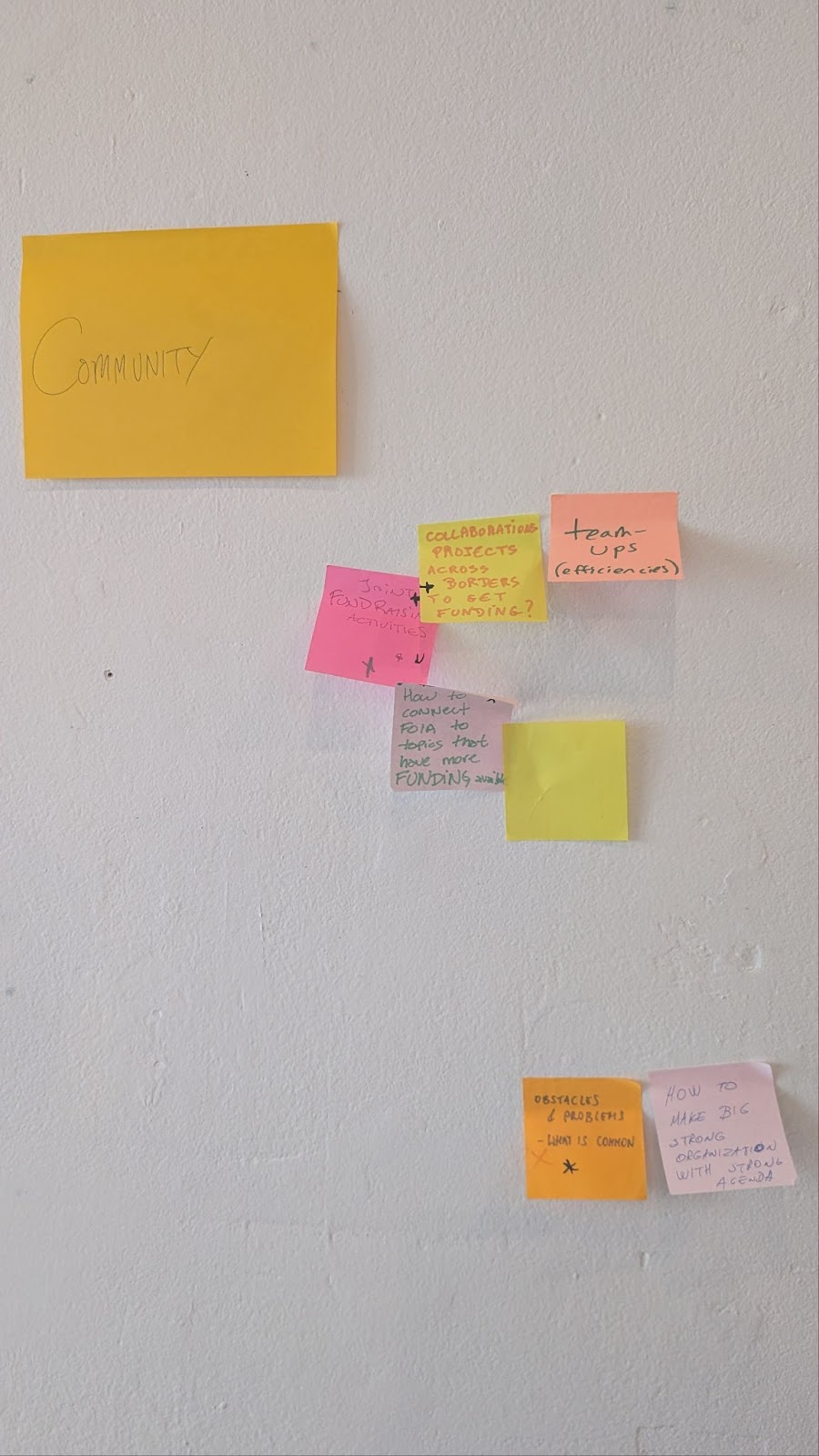

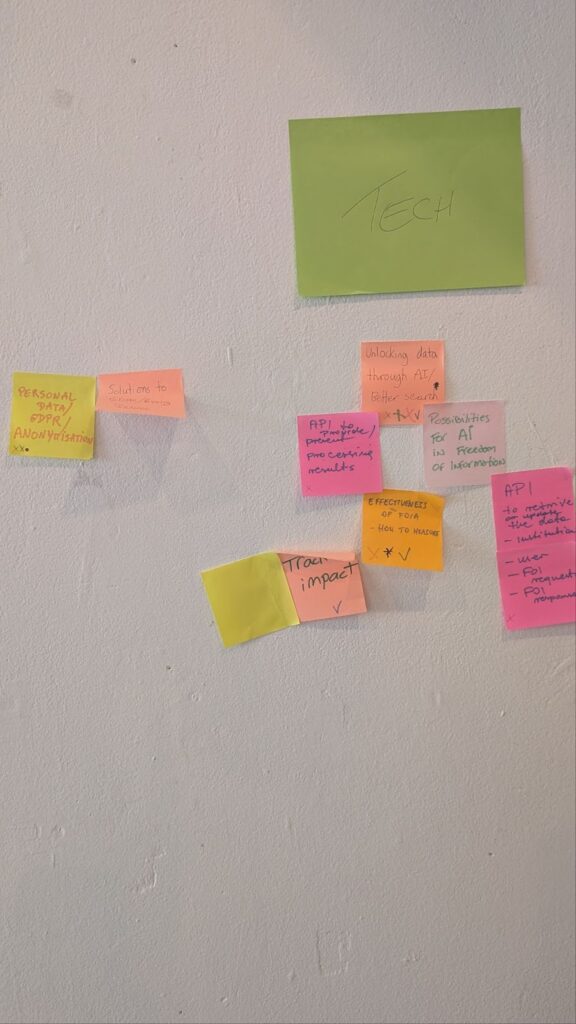

Photo of Post-It note groupings on the unconference wall

Community of Practice Infrastructure

Which kinds of communications infrastructure should we develop to share within the network?

Examples include a monthly call, our email mailing list, more public mailing lists like Right to Information Europe. We discussed better syndicating organizations’ existing communications, like creating an aggregated RSS feed with auto-translation of the content. Several people pointed out, however, that organizational blogs are not a good place to learn about current work. Blogs have become a place to share recent successes but not current challenges. Even the successes are case-specific and country specific.

Community of Practice meetings have been helpful in discussing commonly experienced issues with the tech platforms, but people expressed a need for Freedom of Information program-specific conversations to strengthen the actual FOI programs in their countries.

We generally agreed on the benefits of a community repository for capturing successes and challenges, like using the Civic Tech Field Guide’s free database, which already contains information about many of the projects.

In terms of cadence, there was general agreement that monthly or twice-monthly check-ins are sufficient, as weekly calls are too frequent. Someone shared the Anti-SLAPP coalition’s structure as a productive example: a monthly update meeting, with thematic groups and sub-committees meeting more often as needed.

Participants desire structured and focused meetings, as they have many different activities underway. ‘What’s going on’ lately?’ is too broad a prompt. Participants enjoy the current ‘Last wins’ section of the monthly community call, as hearing uplifting stories from similar organizations is a great rejuvenator.

Another idea is to simply solicit moment-in-time snapshots of what you’ve been working on in the past hour. At first the answers might not seem relevant, but over time you could glean interesting trends and a high-resolution picture of the network’s activities.

When facing a challenge, participants would like to know how other groups are tackling the same problem. Who’s the right person in the network to talk to about it? Even naming the problems people are working on would be a good start.

One idea is to hold a real-time vote on what the meeting topic should be, to ensure the meeting topic is a good fit for current priorities. We could regularly draft a short list of problems and vote on them. This reminded me of MoveOn’s rolling priority council, where a sample of their membership votes on the group’s priorities for a time period (but at a much smaller and more manageable scale).

Team-ups

A central reason for being for the Community of Practice is the efficacy and efficiency that could come from more coordination between groups. For example, people expressed interest in teaming up for lobbying for stronger Freedom of Information programs, and sharing research efforts. (We’ll cover fundraising team-ups in the funding section below).

A representative from a Global Majority country shared that it really helps their work when so-called “Global North” partners publicly call out harmful trends. Those trends are often happening in several countries, and these partners can help draw attention to them.

Given that most Access to Information groups are focused domestically, language translation is one barrier to teaming up internationally. A translation step is often necessary. Machine translation is getting better and better, and we shared other language-bridging communication efforts, like the network of volunteer translators powering the Global Voices citizen media network and the emphasis g0v News has placed on ensuring English translations of their current work.

Participants suggested that the CoP’s existing ‘shared tech problems’ conversation is helpful, but that they desire a common project to work on together, perhaps in a federated approach. For example, CoP organizations could coordinate in advocating for stronger European Union regulation on Access to Information.

Local relevance varies, though, as some participating organizations don’t directly submit Freedom of Information requests themselves, but rather support national FOI processes.

Another suggestion where the community could collaborate is in researching the effects of comparative FOI laws between countries. This would entail not just analyzing textual differences in the laws themselves, which has been done, but also the impacts of the laws. For example, what impact has GDPR had on FOI request work?

We agree that beginning to track generalizable challenges, best practices, and tactics would be beneficial, even if some information is specific to work in individual countries.

Network-wide impact tracking

We discussed streamlining our network’s impact tracking. Are there high-level metrics and performance statistics organizations could easily get and share so that we could aggregate them at the network level? Given the difficulty of requesting information from governments, this project would need to show gaps in the data, as well.

For example, 3 basic numbers would provide a baseline starting point: how many requests were facilitated, how many got a reply from the government, and how many of the replies were successful. It’s possible (in some places) that showing authorities the gaps in information could help improve the administration of the Access to Information processes.

Several participants expressed that the official government Access to Information statistics where they operate are unreliable. For example, in some places the government official tasked with answering the access to information request is the same person who decides if the request was successfully answered. Unsurprisingly, civil society organizations often disagree on whether a request was genuinely and sincerely responded to.

Government challenges

Some public sector offices actually blacklist the Access to Information organizations, blocking their IP addresses and sending their messages (which were generated by citizens) directly to spam folders.

A deliverability workshop could be a useful resource for this network. But the broader challenge of unresponsive governments violating their own laws remains.

One Access to Information group was forced to sue the government, won the case, and still, the government responded aggressively even after courts ruled against them, threatening to disregard the organizations’ efforts on behalf of citizens.

Communicating Access to Information to the public

How do we communicate Freedom of Information to “normal people”? These programs and platforms are meant to help journalists, data-minded people, and regular citizens alike. How do we tell the story of what can be done with access to info tools, why it’s good, and the impact they can have? Driving usage of Access to Information tools requires more people understanding that they exist and how they can use them. One challenge in doing this well is to zoom out from our professional level of detail so we can start with more basic explanations of what these programs and tools can do for their users.

For example, a public information website in Poland helps citizens visualize the entire information request process and where they currently are in it.

Working with journalists to promote Access to Information awareness

One approach that drives public awareness of Access to Info programs (and the civic tech tools that enable them) is when journalists who rely on the information publicly attribute the platforms as their sources in their stories. Web-savvy and data-driven media publications like ProPublica do a good job of sharing their data methodologies behind major investigations, and often publish open data as part of a larger investigation. In Brazil, the FOI process went from relative obscurity to being featured in one of the ten questions asked in the nation’s presidential debate.

In France, Ma Dada requested copies of President Macron’s actual salary payslips. Although the President’s salary is already well-known information in France, the hook of the payslip document was compelling enough for journalists to run with it. They did a 4-page dossier spread on Freedom of Information in France to inform the public on the process behind how they got the President’s actual payslip documents, educating citizens that the Access to Information program exists and that they can use it themselves.

In other cases, however, groups have found that if the information unlocked informs a very juicy news story, the role of the Access to Information process gets downplayed in the coverage.

To promote journalistic use of their tools and services, some organizations provide media outlets with interesting data obtained from their own FOI requests. Then they teach journalists how to submit requests themselves, and host workshops. This can be time-intensive, as some journalists “want everything pre-chewed” and don’t know how to do basic data analysis tasks like filtering the data set.

Sometimes the government’s response window (for example, three weeks) doesn’t always map well to journalists’ need to file 5 stories per day. Journalists want the information right now. To adapt to this reality, one organization goes and gets the data through the FOI process themselves, and provide it to journalists to whet their appetites. Only then, after they’ve shown why the FOI process is valuable to them, do they offer workshops.

The organization’s only requirement is that journalists who receive their exclusive information cite the group and the Freedom of Information program as their source in order to help popularize the practice. This approach has become incredibly popular with journalists, as tens of thousands subscribe to and read the organization’s free email newsletter.

Over time, Access to Information groups have seen that some of the types of data requested repeat on an annual basis, or recur seasonally. Noticing these trends helps the organizations proactively flag the data for journalists when those data become available.

Slick platforms for sick programs

In Greece and other countries, the government’s underlying official Freedom of Information program doesn’t work well, so convincing citizens to participate is complicated. Civil society organizations are at risk of helping legitimize a broken system by directing citizens to it. And if government authorities never answer access to information requests, it reflects poorly on the civil society organizations and their web platforms. An unsatisfying process with no reply or delayed replies or unsatisfactory replies from the government turns citizens off from participating in FOI programs. We need solid underlying legal frameworks for FOI to be successful.

When every access to info request must go to court to be enforced, it exhausts the resources of small civil society organizations doing the work, even when they win the cases. If journalists and everyday citizens can’t or won’t take unresponsive cases to court, the freedom of information concept fundamentally doesn’t work.

One organization offered a clever tactic they used to get government officials responding. They built a relationship with an incoming mayor, guaranteed press coverage if they responded to the access to info request, and then created a sense of urgency where another mayor could answer a request first and earn the media attention. This combination got the ball rolling for other officials to respond to future access to info requests.

Prioritizing critical information requests

Another challenge with government responsiveness to access to info requests is that they may respond to innocuous questions, like the total area of parks in a city. But on burning issues of great political importance, like those involving refugee camps, some governments are less responsive. Likewise with questions involving party financing or potential government corruption. These so-called “polemic” issues are key to A2I programs and get other journalists inspired to use the FOI process.

Access to Information groups depend on better-funded media publications to help fight this fight.

Access to Information groups can help point journalists to the types of information they can look for to inform an investigation. Over time they develop experience identifying the types of documents that can provide an autopsy of how a specific government decision took place. For example, users can request government meeting diaries and meeting minutes leading up to the decision.

One way this network of Access to Information groups could drive usage amongst journalists is with a concerted marketing effort to inform online journalism resources about their platforms and workshops.

In Poland, an organization assists their users with pre-written templates for filing complaints, or what to say when the government doesn’t answer, or only partially answers, or misunderstood the request, or outright denies the request. They’ve also created an easy to understand interactive flowchart to help users understand where they are in the Access to Information process and what their next moves could be. Their repository of FOI-related knowledge spans 12 years, including related legal judgements and cases. It also benefits the organization by performing well in web searches for the topic.

Another organization created a wiki for journalists, offering guidance on topics like what to do next when the government denies a request.

Finding funding

We candidly shared which FOI projects have funding, and where they were able to source it. Some organizations sell their technical services to get grants that support their work. Many rely on foundations and US-based funding, like the National Endowment for Democracy and USAID. The 2024 US election results could adversely impact these funding sources.

The Patrick J McGovern Foundation is exploring the use of AI for transparency. Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust is seeking to understand ways marginalized communities in the UK can benefit from FOI programs and services. The Norway Liechtenstein Iceland fund isn’t currently open, but has funded some A2I work in the past. The next fund is in 2 years.

In Poland, taxpayers are offered the option to divert 1.5% of their taxes to charity. Many people choose to fund an Access to Information group while filing their taxes, and this ends up representing over 50% of one organization’s budget.

We discuss the European-wide funds, and ways European partners could team up in applying for them. This Community of Practice could help individual groups through project collaboration and applying for funds together. To do so, we’d need to understand where overlap exists, and where different organizations complement each other’s strengths and focuses.

The community could also work together in other ways by forming a circular economy. For example, if one organization is particularly adept at data visualization projects, other groups with funding to contract that work could hire from within this Community of Practice network.

Some Access to Information projects are entirely unsupported, but their host organizations keep them going anyway due to the importance of that work.

Other funders include the Google News Initiative, US and Canadian consulates in countries, German foundations, big individual donors in Brazil.

mySociety’s Whatdotheyknow and Alaveteli Pro services and subscriptions bring in revenue that supports the work. Their for-profit arm, SocietyWorks, sells tools to local councils as well. Another revenue opportunity is offering FOI-based consulting to local councils.

One organization partners with refugee and migration NGOs in Greece, showing how access to info cuts across many different domains.

Someone suggested hosting a closed, online donor showcase event where we could present the other groups in this Community of Practice to funders. For example, the Global Forum for Media Development hosted 25 journalism donors to convene for a pitch day, which generated further funding conversations.

Funder perspectives

A couple of funder friends sat in on our gathering and responded candidly to our fundraising conversation and the difficulty of funding democracy work right now. They also shared that for foundation program officers, communicating the specific role that civic tech platforms play in equipping journalists with critical information to their boards isn’t a simple task.

A major funder has left the democracy arena, and their departure has had outsized effects on the total pool of resources available for this type of work in Europe.

Due to this paucity of resources, remaining funders have shifted their strategies to fund pan-European projects wherever possible despite the reality of individual nations’ needs. For this reason, we were advised to include a minimum of 5 applicants from 5 different EU countries when applying for EU funding.

The funder suggested Access to Information organizations team up with media outlets for funding and offer a generous split to publications. They argued this would provide core funding while also demonstrating their relevance through the journalists’ immediately applied work. The news stories are often what communicates the value of the underlying Access to Information work.

They also shared some other potentially interested funders, including the International Press Institute, a consortium of journalism funders, and Allianz Stiftung in Germany. Many journalism funders, they said, are unaware this Access to Information community is doing all this unpaid work to assist journalists. The concept of Access to Information platforms is too abstract, they said, compared to funding something straightforward like journalism.

Governments battling journalists over legally-mandated access to information is a form of harassment of journalists, they said, and this type of legal bullying and lawfare are a better fit for journalism funders.

Wealthy individuals are another funding source. One strategy to get to them is through the philanthropy advisors who guide these high net worth individuals, as they’re less difficult to find. But wealthy individuals can be less reliable long term, our ally said.

They suggested we make ourselves visible at journalism conferences whenever possible, such as the International Journalism Festival in Perugia. If we do convene funders for a pitch day, we should agree in advance that the event won’t result in a flood of funding requests to attendees immediately following the event.

Funder education is necessary, they said. Another funder ally recommended sharing the fruits of Access to Information programs with funders. On specific topics like climate action, we should collaborate with organizations doing the other side of this work. A hazard with this approach, though, is that if you invest heavily on one topic, like climate change, your organization ends up being labeled as specific to that single issue.

When program officers are limited to making only one grant per topic, there’s a strong incentive to support as many organizations as possible with that grant. We could identify a dedicated funder or two and team up with one grant (and multiple sub-grants) to make it easier for funders to support us.

Developing our Community of Practice

One successful FOI grant team-up paired three organizations together to cover different parts of the deliverables: Access Info covered the legal side, Fragdenstaat covered implementation, and mySociety led the technical component.

As we build connections within our network, through knowledge-sharing and -capturing and learning by doing, we could become more adept at teaming up for bilateral funding in similar ways.

As we capture outputs and documentation for the entire network, we can better make the case for the peer practitioners of this work. For example, Fragdenstaat led a Europe-wide investigation into national pensions going to ex-Nazi officials in different countries. We could leverage our network of national Access to Information sites and their media relationships to amplify that investigation across our individual borders.

Next actions

We discussed establishing a regular communications routine, to make monthly calls more effective with real-time voting on the agenda for discussion. We also considered how to get started collecting network-wide impact metrics, even with the known caveats around missing data.

I offered the Civic Tech Field Guide’s open database as a place to create a gallery of the Access to Information Community of Practice’s projects, and to inventory ongoing challenges and wins within the network.

To get started with fundraising team-ups, we could make a rubric or checklist of what kind of work each organization does, and set a monthly routine of evaluating open grant programs through that rubric.

As one participant put it, “Freedom of information is a human right. Without it, you can’t have rule of law, democracy, or accountability of power.” Joining this network convening of international Freedom to Information groups helped me understand the important role they serve in government oversight, as well as the precarious position they’re in with regards to funding and government adversaries. I’m grateful this Community of Practice exists to identify ways to work together and strengthen each other’s efforts and organizations.